- Home

- Polites, Taylor M

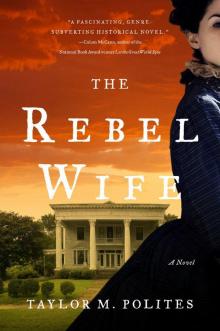

The Rebel Wife

The Rebel Wife Read online

Praise for

THE REBEL WIFE

“This is a wonderful first novel—passionate and brave. It removes the skin of an era and questions so many of the tropes that hover around nineteenth-century southern American literature. It was Faulkner who, in the twentieth century, talked about the voice of Fiction being inexhaustible. Taylor Polites has extended our narrative reach into yet another time. A fascinating, genre-subverting historical novel.”

—COLUM MCCANN, author of Let the Great World Spin

“Taylor Polites’s The Rebel Wife is the love child of William Faulkner and Margaret Mitchell and sister to charlotte Perkins Gilman’s ‘Yellow Wallpaper.’ A gripping Look at Reconstruction-era Alabama through the mind of one flawed, desperate woman.”

—LENORE HART, author of The Raven’s Bride and Becky

“Taylor Polites’s extraordinary novel has all the qualities of a southern Gothic but is so very much more. This brilliant new writer has taken an age-old genre and turned it on its head. . . . In a nail-biting tour de force, Taylor Polites has brought the 1870s to life before our eyes with impeccable research and attention to detail. This is a book that exposes ancient myths and will endure and be talked about for years to come.”

—KAYLIE JONES , author of Lies My Mother Never Told Me

“The Rebel Wife takes us to the time when one who suffered through the civil War was left to sort through the debris in order to start again. This story hums with suspense. More great discussion for the book clubs!”

—KATHLEEN GRISSOM, author of The Kitchen House

“The Rebel Wife bears comparison with flannery o’Connor’s and William faulkner’s prose, with the exception that Polites cherishes few illusions about Lost Causes. The failure of Reconstruction meant the deferral of full rights for the former slaves for a full century. This stunning debut novel looks without flinching at one of the enduring shames of our American history, in prose that will linger long after you close its pages.”

—DAVID POYER , author of That Anvil of Our Souls and The Towers

BRIMMING WITH ATMOSPHERE

AND EDGY SUSPENSE, THE REBEL WIFE

PRESENTS A YOUNG WIDOW TRYING

TO SURVIVE IN THE VIOLENT

WORLD OF RECONSTRUCTION ALABAMA,

WHERE THE OLD GENTILITY

MASKS A CONTINUING WAR FUELED

BY HATRED, TREACHERY, AND

STILL-POWERFUL SECRETS.

Augusta Branson was born into antebellum Southern nobility during a time of wealth and prosperity, but now all that is gone, and She is left Standing in the ashes of a broken civilization. When her scalawag husband dies suddenly of a mysterious blood plague, she must fend for herself and her young son. Slowly she begins to wake to the reality of her new life: her social standing is stained by her marriage; she is alone and unprotected in a community that is being destroyed by racial prejudice and violence; the fortune she thought she would inherit does not exist; and the deadly blood fever is spreading fast. Nothing is as she believed, everyone she knows is hiding something, and Augusta needs someone to trust. somehow she must find the truth amid her own illusions about the past and the courage to cross the boundaries of hate, so strong, dangerous, and very close to home.

Using the Southern Gothic tradition to explode literary archetypes like the chivalrous southern gentleman, the good mammy, and the defenseless Southern belle, The Rebel Wife shatters the myths that still cling to the antebellum south and creates an unforgettable heroine for our time.

TAYLOR M. POLITES received an MFA in creative writing from Wilkes University, where he was awarded the Norris Church Mailer Scholarship. A native of Huntsville, Alabama, he now lives in Providence, Rhode Island. You can visit his website at www.taylormpolites.com.

MEET THE AUTHORS, WATCH VIDEOS AND MORE AT

SimonandSchuster.com

·THE SOURCE FOR READING GROUPS ·

JACKET DESIGN BY CHIN YEE LAI

JACKET PHOTOGRAPHS: WOMAN BY RICHARD JENKINS,

BACKGROUND © PLAINPICTURE/RETO PUPPETTI,

HOUSE © VISIONSOFAMERICA/JOE SOHM/GETTY IMAGES

COPYRIGHT © 2012 SIMON & SCHUSTER

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2012 by Taylor M. Polites

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition February 2012

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Designed by Jill Putorti

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Polites, Taylor M.

The rebel wife / Taylor M. Polites.

p. cm.

1. abama—Fiction I. Title.

PS3616.O56756 R43 2011

813’.6

2011007100

ISBN 978-1-4516-2951-4

ISBN 978-1-4516-2953-8 (ebook)

To Kaylie Jones, mentor and friend

Thank you for purchasing this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to bonus content, and info on the latest new releases and other great eBooks from Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Acknowledgments

Author’s Note

Selected Bibliography

The

Rebel Wife

One

I KNOW THAT ELI is dying.

Rachel said the rattlesnakes were a bad sign, but that doesn’t signify. The Negroes give so much credence to conjuring and signs. But there is something about Eli. He looks so much like Pa before he died. Eli trembles in his bed like Pa did. He has the same fever in his eyes. Losing Pa was terrible, but I don’t feel that with Eli. He is not a bad husband, but it will not be like when Pa died.

When Eli came home on horseback, the heat had covered him in sweat. The humidity hung in the air like wet sheets shimmering in the sunlight. Simon had uncovered a nest of snakes beside the carriage house by the apple trees. Rachel and Emma were wild with fear. They closed themselves up in the kitchen. It became so hot the bricks seemed to sweat. John helped Simon kill the snakes with hoes while Rachel called to John from the kitchen window l

oud enough for the whole town to hear, shouting at him to keep away, to think of their boy, repeating over and over that it was a bad omen. Simon ignored them as if he had no fear at all. His black skin was dotted with tiny beads of sweat from the heat or maybe that was fear. He hacked at them while they shook their rattlers and coiled around each other in a solid writhing mass. Simon warned me to stay back, but I wanted to see them. And then Eli came riding up the lane almost hanging off his saddle.

He drank water straight from the pump, lifting the lever and heaving it down as he bent over it, the other hand extended, waiting for the rattle of the pipe until the water splashed over his palm. The sunlight glittered in it as he threw it on his face. He drank it in gulps. Simon left the dead snakes and spoke with him. He helped Eli into the house and left the horse for John.

Eli is twenty-five years older than I, but he gives the impression that he could live forever. He has a sureness of youth about him in spite of how ungainly he is. He is imposing but not handsome. Never handsome. His waxy scalp shines through his thinning hair. His nose is bulbous. His jaw sags with awful, long whiskers. He wears odd Quaker hats to keep the sun off or his skin will splotch red.

He barely said a word through supper last night and picked at the cold mutton and pickles Emma laid out. He complained of the odor of her canned tomato relish and the early greens. His wheezing drove me to distraction. He stared at his plate, red-faced, breathing hard as if it took all his concentration. I had to scold Henry for shoving his sopping biscuit into his mouth.

He was dazed when he took to his bed—our bed. He perspired to excess but would take no water. Dr. Greer’s visit was hardly reassuring. He came late and said it was some fever that would pass. He recommended cold compresses and tartar emetic to increase the sweating, even though the bedding was already soaked. And a bleeding tomorrow, he said.

Simon gave him the emetic mixed with molasses. Emma and Rachel kept wet cloths on his forehead. Then I had my turn, sitting with the lamp low, watching the rise and fall of his chest and the dull rattle from each exhale. Just once he awoke, but he didn’t speak. He searched the room with his eyes, searching for something, and then he saw me. His hand reached out and I took it in mine, curling my fingers around his without touching his palm, resisting him. I hushed him and pressed the damp cloth against his forehead. I wiped down his chest through the gap in his nightshirt. He closed his eyes and drifted in and out of sleep, disturbed by the spasms brought on by the emetic. I knew then that he would not survive. I know for certain that he is dying.

When Pa died, it was about winter. The trees were already half bare, the lawns brittle and brown. But everything here is so alive. The garden soaks in the sun, thriving in this relentless humidity without the faintest hint of death. The grass is dense and green. The trees are heavy with leaves, drooping with exhaustion. Fat peonies have bloomed, their petals collapsing into so many delicate pieces of torn pink silk on the grass. Tendrils of honeysuckle twine around the thin posts of the back porch, their honey-sweet perfume hanging in the air with no breeze to move it away.

Henry plays on the gravel path. His towhead in the sun is like new hay, a trait he bears from Eli. He is all Eli, with none of the Sedlaw brooding features and dark hair. He squats with a stick in his small hand, poking at an anthill. He has no sense of waiting. He only asked this morning why Papa was still in bed, then shrugged away his concern when Emma came in.

“Come quick, Miss Gus!”

Emma leans from the bedroom window waving a towel. We both look. White turban. Black face. Black dress. White cuffs. And a filthy towel whipping wildly in front of her. No words anymore, just panic on her face. I know what she has to tell me. Thank God she came with me into this house when I married. Mama threw a conniption, but Emma is free to choose as she pleases. Lord knows she was more of a mother to me sometimes than Mama. She chose to come for whatever reason. I didn’t force her.

“Wait here for Mama,” I call back to Henry. My shoes crunch over the pea-gravel path and click against the steps of the porch.

The shadows of the house are cool. A door closes upstairs, but the latch does not click. I mount the step and my heel catches in my skirts. The hem tears. I pull at my dress and grab the banister.

The odor of sweat and rot slithers around me. It swallows me as I climb. I want to retch. What is all this red? Is it blood? I should go into Eli’s room, but this red—red everywhere, smeared on everything. Bowls of pewter and clay are scattered across the hall bench. Blue willow china and cooking pots canter pell-mell over the wood and overflow with wet rags tinted scarlet, dripping red onto the polished hickory, swirling in shimmering iridescent shades of crimson like oil in a puddle. Red smudges the lips of the bowls and pools in their wells. The white door is marked, smeared with red in clumsy fingerprints that are slashes against the gleaming paint. I cannot touch the brass handle of the door. The substance covers it.

I hear Emma’s voice. “You’ve got to keep working at him, Rachel.”

I push at the wood with my fingertips. It swings open slowly. Eli lies panting in his bed, prostrated. He is stripped of his clothing, appallingly naked against the white sheets. Emma, Rachel, and Simon all work at his body. The redness drips from his temples like sweat. It seeps from his armpits and the wrinkled folds of his neck. His skin is tinged watery pink. The bed linens are soaked with jagged marks of red saturation around his body like a grisly halo. He wheezes pathetically as the servants soak up the fluid with their rags and wring it into bowls. More red seeps through his skin, dripping down his arms and legs as Simon lifts each one, pushing a red-soaked rag across his limbs. The fluid falls from his face, collecting in pools around his eyes and spilling onto the sheets as he trembles. Bowls filled with bloody cloths sit on the bedside tables. The servants cannot wipe it off quickly enough. Their work is frantic.

“I won’t,” Rachel says. She holds her hands away from herself as if they are not hers.

“Rachel, hush,” Emma says, cutting her eyes between us.

“I won’t, Emma,” she says. “The devil’s done bit him on his heel to bleed like that. I won’t!”

Rachel rushes around the bed and past me, wiping her hands on her apron. They leave pale pink streaks across the white cloth. Emma and Simon turn to me. “Miss Gus, Mr. Eli needs the doctor,” Emma says.

But I am paralyzed. I will my feet to step forward, but they refuse. I can only watch him. I cannot pull myself away. What is happening to him?

His eyes have an unseeing wildness as they search the satin starburst of the bed canopy. They roam in wider circles until finally he stares into my face. He lifts his arm just barely, too weak to move. He groans with a terrifying rattle in his chest. A gurgling sound.

Simon looks at me. “He wants you, ma’am. He wants your hand.”

Eli’s pupils are dilated to large black spots in pools of red, staring at me as if he wants to say my name. He reaches for me. I lean on the door frame. I think I am going to faint. My heart is thudding in my throat so hard I can’t breathe.

“I’ll tell John to fetch the doctor,” I say. I fall out of the door and hold the banister with both hands, looking down the well of the stairs. My head spins along their curve. All of my insides feel as if they will come out.

Simon is beside me. He has left Emma alone with Eli. He puts a hand on my arm. “Miss Gus,” he says. His eyes are hard. “Did you see if Mr. Eli had anything with him when he came home?”

“Simon, take your hand off me.”

“I’m sorry, ma’am.” He pulls his hand back. “Mr. Eli should have had a package with him yesterday. I think it might have contained some money.”

“Don’t be ridiculous. Eli needs a doctor right away, and you come asking me for money?” It’s a wonder that Eli trusted Simon.

“I think it’s important. Mr. Eli would want to know that it was safe.” He steps back and his face loses its expression.

“I’m getting the doctor for Eli. I think that’s what is im

portant. If you want to help Eli, then you should be with him. Emma’s in there all alone.”

We both look through the open door. Emma is on the far side of the bed, looking over Eli while he wheezes. Simon’s face becomes stern. These servants. Thank God for Emma.

“Yes, ma’am,” he says. He nods and goes back to Eli’s side.

Rachel had better not have already frightened John with her stories. He’ll have to fetch the doctor either way.

The wall clock is ticking by the small hours. Emma and Simon are surely asleep in their beds, although a light from Simon’s room over the carriage house glows against the thin curtains. He keeps his lamp lit, a faint flickering glow half hidden by the catalpa tree. Perhaps he is awake and waiting. Perhaps Emma is in her attic room waiting for a word from me. After this horrible afternoon, we are all waiting. His sickness—whatever it is—overwhelmed him so quickly.

Eli’s breathing works in a faltering heave and sigh. The lamplight has faded. The oil must be almost gone. At least the bleeding has stopped. Thank God it has stopped. But the scarlet-stained sheets are still under the blankets Greer had us put on Eli to keep off the chill.

How stunned Greer was when he came again, watching the sweat and blood pour off of Eli. His features seemed to fall in on themselves.

“I am sorry, Gus,” he said. “I have seen terrible things. I have done them, Lord knows. We had to do them. We did what we could to save those boys. Poor innocent boys.”

What could I do but nod? Greer is such easy prey to his memories of the war, unable sometimes to speak of anything else. Unable to help himself. We looked down on Eli’s suffering face, both of us struck dumb.

The Rebel Wife

The Rebel Wife